The sector may be on a collision course with a recessionary ‘iceberg’ that could see a sink below pre-COVID levels.

The soaring container shipping industry may soon be on a collision course with a recessionary ‘iceberg’ that could see the industry sink back down to pre-covid levels. As it stands, the waters look calm and tropical. Maersk, one of shipping’s biggest players, has raised its annual profit forecast for the third time this year to an impressive US$31 billion, up from US$24 billion. Drewry, an independent maritime research consultancy, estimates that the industry as a whole will make operating profits of US$270 billion this year, a 10 fold increase from 2020. This being the result of soaring demands for COVID-19 related products like masks and personal protective equipment as well as increased consumer spending.

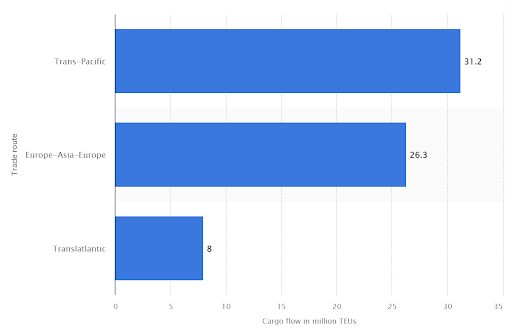

The seas ahead however look unsettling. The unending war in Ukraine, sharp increases in global energy and food prices, escalating rates of inflation and China’s confounding zero-covid policy are slowly but surely steering the container shipping industry towards the figurative glacial mass. A good indication of this lull is assessing one of the world’s most frequented shipping routes – the Trans-Pacific trade route. Figure 1 shows the dominance of this Asia and North America route with over 30 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) flowing between the two continents.

Figure 1: Estimated containerized cargo flows on major container trade routes in 2021

Source:https://www.statista.com/statistics/253988/estimated-containerized-cargo-flows-on-major-container-trade-routes/

Source:https://www.statista.com/statistics/253988/estimated-containerized-cargo-flows-on-major-container-trade-routes/

According to Raymon Krishnan, president of Singapore’s Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society, the spot rates for the Trans-Pacific route have begun slipping – from an eye watering US$16,500 per container down to below US$5,000. Some are forecasting this to get to as low as US$2,000 per TEU which would be a revival of 2020 levels. The same can be said for forty-foot equivalent unit (FEU) containers, with the Freightos Baltic Index (FBX) experiencing a dramatic spot rate drop from US$20,000 to US$2,361, all in the space of a year.

HSBC has given a more accurate outlook of the industry stating that spot rates will hit a trough by mid-2023 with profits set to drop by as much as 80% in 2023/2024.

A supply downturn of this magnitude in such a short period could have serious consequences for liner operators. A precarious global economic outlook, stemmed by rising interest rates to curtail inflation, will add pressure to the industry as governments purposefully cool their economies.

Globally, containers in service will decline from 50.8 million TEU in 2022 to 49.3 million TEU in 2023 with annual production slumping to an estimated 497,000 TEU, a number only slightly above that recorded during the 2009 global financial crisis. This is compared to the 7 million TEUs that were produced in 2021 to meet soaring demand.

After a dismal decade, container liners took advantage of their pricing leverage whilst the going was good. Evidence can be seen that some liners deployed their huge cash hoards cautiously, bracing for another potential 10-year slump. A wise decision. As the economic cycle turns, possibly to levels seen in 2009, shipping is bound to lag, straining the balance sheets for some carriers. Drewry has projected a massive year-on-year capacity growth of 34% should the industry decide not to act on reducing its supply, compared to a paltry 1.9% demand growth forecast. This overcapacity simply cannot be ignored.

To avert a potential crash, and to reduce this 34% to a more palatable number, liners would consider three options for a smoother sail into 2023.

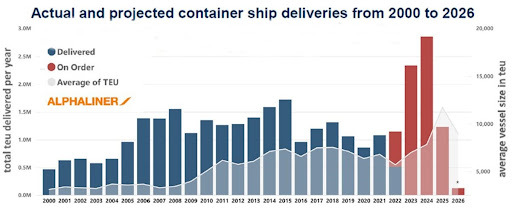

Firstly, scrapping older ships and delaying new ones. Drewry suggests decommissioning 600,000 TEUs next year, 2.5% of end-of-2022 fleet capacity. To maintain this reduced capacity, taking delivery of new ships will need to be delayed. Why? The current containership orderbook stands at a record 7.1 million TEUs over the next 3 years – see figure 2. The majority of the TEU’s on order will be delivered in the next two years: 2.34 million TEUs in 2023 and 2.83 million TEUs in 2024. With that much capacity, the market will struggle to absorb all these new ships.

Figure 2.

Source:https://www.freightwaves.com/news/tidal-wave-of-new-container-ships-2023-24-deliveries-to-break-record

Source:https://www.freightwaves.com/news/tidal-wave-of-new-container-ships-2023-24-deliveries-to-break-record

Secondly, idling tonnage. Liners have the option to idle their vessels, thereby reducing capacity to prop up prices. The method was used during the 2009 global financial crisis where nearly 10% of the globes fleet were moored. This provides a window for these companies to repair and conduct maintenance on their fleets, especially those that are deciding on delaying the delivery of new vessels and need current ones to last a few years longer.

Lastly, blank sailings. A blank sailing means a vessel is skipping one or several ports, or that the entire route is cancelled altogether. This process helps drastically reduce capacity, but liners must be careful as regulators will be scrutinising their adjustments to ensure national economies are not being damaged for the benefit of a carrier.

Implementing these three options, according to Drewry, would significantly reduce the 34% overcapacity figure to single digits. Hopefully enough for the industry to weather the storm and sail again into calmer, profitable waters.

To check out the full range of shipping containers available at Pickles, click here.

11 Nov